Get Back in the Box: The Hidden Architecture of Metaphysical Presuppositions in Science

While metaphors love to roam free, some things are best kept in their box, or their context, it is especially relevant when we talk about presuppositions and referential systems in science.

Metaphysical presuppositions are like power outlets—you can plug all kinds of tools into them, but only if you know which current they carry. Confuse the voltage, and even the most elegant device burns out. Keeping things within their proper referential system isn't about limiting thought—it's about making sure it runs on solid ground. Yet, in much of contemporary scientific discourse, these presuppositions go unnoticed. This article’s aim is to bring those metaphysical scaffolding into clearer view—and put them back in their place (kindly)—so we can ask better, more honest questions.

“We habitually speak of stones, and planets, and animals, as though each individual thing could exist, even for a passing moment, in separation from an environment which is in truth a necessary factor in its own nature. Such an abstraction is a necessity of thought, and the requisite background of systematic environment can be presupposed. That is true. But it also follows that, in the absence of some understanding of the final nature of things, and thus of the sorts of backgrounds presupposed in such abstract statements, all science suffers from the vice that it may be combining various propositions which tacitly presuppose inconsistent backgrounds. [...] All reasoning, apart from some metaphysical reference, is vicious.” (A. N. Whitehead, Adventures of ideas)

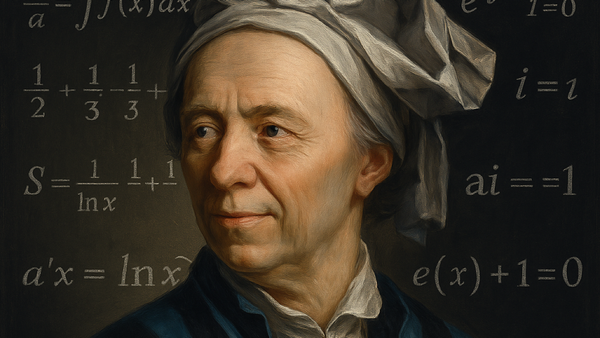

What Are Metaphysical Presuppositions?

Metaphysical presuppositions are background assumptions taken for granted about reality and existence that underpin all intellectual inquiry, shaping both the questions we ask and the answers we accept. They are the implicit conceptual agreements we rely on to make sense of empirical evidence, philosophical questions, and theoretical frameworks.

Wilfrid Sellars called the belief in unfiltered, pure data the “myth of the given.” Every observation, even in science, is theory-laden, constructed through conceptual filters that include metaphysical assumptions.

These presuppositions go unnoticed precisely because they are so close to our belief about the world, often heard repetitively and inherited from teachers. That ‘reality is measurable,’ ‘what cannot be observed does not exist,’ or ‘spacetime is an illusion’—these are not conclusions, but inherited choices.

Blurry Boxes: Between Methodology and Ontology

There is a growing global and intellectual trend that we actively embrace in our research at the Science & Philosophy Institute: a turn toward interdisciplinarity and trans-boundary thinking as a means of reframing problems and uncovering novel insights. Yet the philosophical and interpretational edge scientists play at requires a precise rigor to avoid conflating methodological convenience with ontological commitment.

In their book The Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience, Bennett and Hacker critique the tendency to conflate phenomenological qualities with physical mechanisms. For example, in neuroscience, once we understand that color perception arises from the reception of electromagnetic waves at various frequencies, some neuroscientists venture to claim that qualities such as color are nothing more than mental constructs. According to this view, the “real” world is entirely unlike the one we perceive, and colors have no individual existence outside the brain. But identifying a mechanism does not amount to disproving the intrinsic existence of a quality or property. This is precisely where the importance of clear definitional boundaries comes in: is ‘red’ being defined phenomenologically—as a quality of lived experience—or physically, as a molecular or electromagnetic arrangement?

Physics is no stranger to this kind of conceptual leap. In the Many-Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, it is often said that the universe "splits" into multiple versions of itself whenever a quantum event occurs. This idea comes from a mathematical process called decoherence, which helps explain why certain outcomes appear classical by suppressing interference between quantum states. What actually happens is that the wavefunction evolves into a superposition of distinct, non-interacting branches, each corresponding to a different possible outcome. However, interpreting these branches as countless physical worlds springing into existence is a philosophical jump, confusing a mathematical tool for a physical ontology.

Re-Situating Presuppositions in Their Referential Systems

When claims become confused for conclusions we wobble dangerously on the land of metaphysical doctrine. To "re-situate" a presupposition into its definitional referent means to recognize it as a context-bound heuristic, not a universal truth. Philosopher Nancy Cartwright, with her critique of "one-size-fits-all" scientific laws, shows the importance of local, context-sensitive metaphysics.

Back to its origins: Where did this presupposition come from? What discipline did it emerge from? What conceptual or societal needs did it serve?

Neighbors systems: How does this presupposition function in different disciplines? For instance, causality means something quite different in classical mechanics than in psychology. And energy collects almost as many definitions as there are theories in physics

Change: Change is law in nature—and it can be just as beneficial in our beliefs. Adjust your presuppositions as you see fit.

Conclusion

Perhaps the challenge of our time is not a lack of data, but a lack of attention to where our knowledge begins. This is also an invitation to bring attention to the words we chose, the expressions we carry, and how they shape our comprehensions. This practice of reflective awareness is not for doubting science; it grounds our knowledge more deeply, checking its solidity and, perhaps, revealing its beauty.