How Do We Make Physics a Relational World?

In the quest to understand the universe across all scales, certain concepts have sparked particular fascination during my early studies for their radical potential in foundational physics—among them, the idea of causation, holographic principles, relationalism, and nonlocality. What makes these ideas so compelling is that they speak directly to the ‘edge’ of our knowledge—a boundary or interface where our understanding grows, deepens, and transforms. In a universe that we try to perceive as an interconnected whole rather than an ensemble of isolated blocks, an edge becomes a potential for relation, a space in which new interactions and fresh perspectives can emerge.

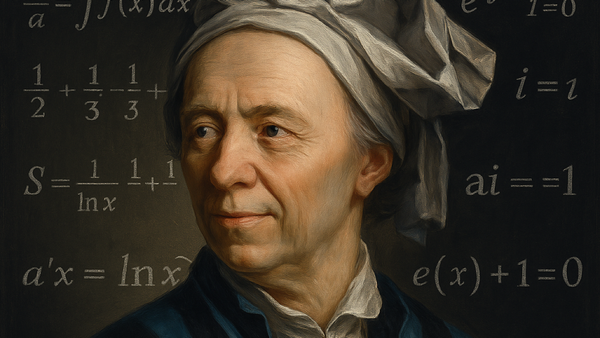

The name relationalism was raised by Gottfried Leibniz about the notions of space and time in contrast against Newton's substantivalism. And later in Lee Smolin’s work in quantum gravity looking at a relational and dynamical spacetime geometry.At its heart, relationalism is about exploring a novel way of comprehension—changing our interpretative lens to study the ontological role of relational structures. We are not observer A looking at landscape B anymore. The methodology pushes us to include the observer in the studied system, looking at the nature of the relations between things and points of view.

So, how do we make physics a relational world?

1. Abandon the Notion of Absolute “Background”

- Traditional View: Physics often starts with a fixed spacetime manifold (in General Relativity) or an external reference frame (in quantum theory) on which particles and fields evolve.

- Relational Move: Instead, regard space, time, and fields as emergent from underlying relations among fundamental elements or events. No universal backdrop to stand on—everything is in dynamical relation. Loop Quantum Gravity and Causal Sets, for example, both adopt discrete structures (spin networks, partial orders) wherein geometry arises from how nodes or events relate, not from a pre-existing continuum.

2. Make Entities Dependent on Their Interactions

- No “Intrinsic” Physical Properties: A mass, a charge, or a spin is not an absolute label carried around in isolation. Rather, these properties appear only in the context of interactions with other entities or fields.

- Subsystems: Each subsystem has a partial perspective of the rest of the universe, shaped by the causal or informational links it shares. Nothing stands on its own. In Shape dynamics, stemming from Julian Barbour’s work, suggests that only “shapes” (ratios of distances, angles, etc.) carry intrinsic meaning, with absolute scale and absolute time removed. Researchers study “relational cosmology” in which the entire universe evolves according to shape variables, bypassing typical gauge constraints in general relativity.

3. Treat Observers as Part of the System

- No External Observers: A fully relational approach integrates observers (conscious or otherwise) as subsystems subject to the same relational constraints as everything else.

- Measurement Becomes Interaction: Rather than an outside classical observer, measurement is just one more relational coupling: Each observer’s partial view is constrained by their causal past and connection to whatever they’re observing. Nobody is standing outside the whole. In Relational Approaches to Measurement, observers store partial records of interactions, leading to “measurement outcomes” that are observer- (or subsystem-) specific.

4. Use a Network or Graph (Discreteness Option)

- Mathematical Representation: Use networks (graphs) or partially ordered sets to represent fundamental data. Each vertex or node is not a “point in space” but an event or interaction, and edges encode relationships.

- Dynamic Graph: Make it evolve or “grow” according to local relational rules—no external clock or embedding in a continuum is assumed upfront. In Causal Set Theory, for instance, partial order among events stands in for spacetime’s causal structure. Geometry (distances, volumes, curvature) is recovered statistically from how many events are in a region and how they’re connected.

5. Emergent Geometry, Time, and Laws

- No Pre-Set Metric: Distances, angles, and time intervals should come after the relational structure is specified.

- Time as Sequential Updating: Temporal ordering emerges from how new relational links (new events or interactions) appear or “update” the system. Spin Foam Models do something similar in quantum gravity by building 4D spacetime from histories of spin networks. Time is the sequence of discrete spin-network transitions.

6. Incorporate Matter and Energy as Relational Labels

- Energy or Momentum Are Also Relational: In a relational model, mass/energy might label connections in the network, rather than being a free-floating scalar.

- Gravity as Geometry ↔ Energy Coupling: The strength or frequency of certain relational updates can reflect how matter content influences emergent geometry.Smolin's Energetic Causal Sets proposes that each link/event in a causal set can carry momentum or energy data, which in the continuum limit reproduces Einstein-like geometry–matter coupling.

7. Leverage Global Constraints / “Wholeness”

- Balance Local vs. Global: While local relational rules generate dynamics, one can impose a “global coherence” constraint (a wholeness principle) so that all parts remain consistent with each other.

- No Contradictory Views: If two observers interact, they must align on a shared coherent landscape. This contributes to a consistent large-scale universe from local relational “patches.” Some sequential growth models in causal set theory impose conditions that keep the partial order globally acyclic and well-defined, ensuring a coherent emergent spacetime.

8. Aim for Testable Predictions

- Continuum Limits: Show how relational data approximate smooth Lorentzian geometry and quantum field behavior in the large-scale limit. Then identify phenomenological signatures (e.g., small corrections to cosmic expansion, black hole thermodynamics, quantum correlations).

- Observables: Instead of usual fields, define relational observables—counts of substructures, entanglement patterns, adjacency correlators—and see if they match real experiments or cosmological data. Quantum Cosmology attempts to derive inflation, dark energy, or structure formation from relational-labeled networks, then compare with cosmic microwave background or large-scale structure observations.

Conclusion

Making physics and cosmology “relational” means:

- No external, absolute background of space or time.

- All properties, including observers’ roles, emerge from how fundamental elements interact.

- Laws, geometry, and time become byproducts of an evolving network of relationships.

By shifting from fixed backgrounds and systems to relational structures we bridge the dynamics of physics with the perspective of observers. Our exploration of relational principles also opens doors to deeper conversations about how we frame cosmology, challenging us to extend the relational framework to include phenomenological and experiential dimensions.. The freedom to question the very foundations of science—its principles and philosophies—continually shows how a shift in perspective can reshape the way we model the universe. Much like how Bohmian ideas of wholeness view reality as an unfolding process, our relational approach integrates the observer directly into the picture, suggesting that consciousness—or a broader notion of global connection—could be a fundamental element driving the dynamics.

By embracing these intersections—between wholeness, consciousness, and the structural scaffolding of physics—we edge closer to an understanding of reality in which the observer, universe, and the fundamental relational weave are inextricably intertwined.

References

[1] C. Rovelli, Loop Quantum Gravity, Living Reviews in Relativity, 1, 1 (1998).

[2] J. Barbour, B. Foster, and N. Ó Murchadha, “Relativity without relativity,” Classical and Quantum Gravity 19, 3217–3248 (2002).

[3] L. Bombelli, J. Lee, D. Meyer, & R. D. Sorkin, “Space-Time as a Causal Set,” Physical Review Letters, 59(5), 521–524 (1987).

[4] C. Rovelli, “Relational Quantum Mechanics,” International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 35, 1637–1678 (1996).

[5] A. Perez, “Spin Foam Models for Quantum Gravity,” Classical and Quantum Gravity, 20, R43–R104 (2003).

[6] L. Smolin, “Atoms of Space and Time,” Scientific American, 290(1), 66–75 (2004).[7] D. Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, Routledge (1980).